자료: http://www.frbkc.org/PUBLICAT/ECONREV/EconRevArchive/1989/3q89faus.pdf

Jon Faust,

Economic Review, July/August 1989, FRB of Kansas City

※ 발췌(Excerpts):

In the decades following WWII, the U.S. came to be known as the world's largest lender, helping to finance economic growth throughout the world. Indeed, by 1981 the U.S. had amassed $141 billion in net holdings of foreign assets. In the three years that followed, however, U.S. net holdings were totally eliminated and by 1987 this country's net position was a negative $368 billion. The U.S. has now become the world's largest debtor.

There is widespread disagreement regarding the implications of this foreign indebtedness for the economic future of the U.S. Some economists argue that inflows of foreign capital bode well for the U.S., setting the stage for increasing productivity. Other economists counter that this country is borrowing to consume beyond its means and that growth of U.S. living standards will suffer when the bill comes due.

The behavior of investment in productive physical capital will play an important role in resolving this debate. If foreign funds have facilitated an investment boom, then rising economic growth and prosperity may result. On the other hand, if foreign funds are augmenting consumption rather than investment, slower growth in living standards may be in the offing.

This article examines investment as a central factor in appraising the foreign indebtedness of the U.S. The article concludes that investment has been weak in the 1980s and that the combination of weak investment and strong growth of foreign indebtedness could threaten growth in U.S. living standards.

(...)

I. U.S. Foreign Indebtedness: Historical Perspective

The U.S. has undergone a remarkably rapid swing from its status as a net creditor to its current position of indebtedness in the world economy. Chart 1 shows the net foreign indebtedness of the U.S. for the period since 1954. Falling steadily until 1981, bet indebtedness declined in all but 8 years from 1954 to 1981. Since 1981, though, net foreign indebtedness of the U.S. has soared.

Chart 1:

While the surge of U.S. indebtedness has caused widespread concern, history reveals that indebtedness by itself is not an accurate barometer of economic well-being. On the contrary, rising indebtedness has at times been associated with good times, and falling indebtedness with bad times. This section provides a historical perspective for evaluating U.S. indebtedness, indicating that although the U.S. has been deeply indebted before, the speed of the recent buildup is unprecedented.

Defining and measung net foreign indebtedness

Net foreign indebtedness of the U.S. is defined as net U.S. holdings of foreign assets. These net holdings are computed as the dollar value of foreign assets held by U.S. citizens less the dollar value of U.S. assets held by foreigners. For example, in 1981 the net holdings of the U.S. peaked at $141 billion, when the U.S. held $720 billion in foreign assets and foreigners held $579 billion in U.S. assets.

Assets considerd in calculating foreign indebtedness include financial debt (such as bonds), stock market holdings, and direct foreign ownership of physical capital. Thus, what is often caled U.S. foreign "debt" actually inculdes stock market holdings and direct investment as well as financial debt. In this article, U.S. net holdings of foreign assets are referred to as net indebtedness of the U.S.

Referring to net indebtedness of the U.S. as U.S. foreign debt has led to some confusion when the situation of the U.S. has been compared with the debt problems of Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. The debt of these countries, which has attracted widespread attention, is financial debt in the form of bonds and bank loans. Furthermore, the gross debt of these countries is typically discussed, not their net debt.

The figures on U.S. net indebtedness probably overstate the true foreign indebtedness of the U.S. The overstatement arises because the computation of the dollar value of direct investment is based on original purchase price, rather than on current market value. Much of U.S. direct investment abroad took place long ago during the buildup of net foreign assets before 1982. The value of many of these assets has appreciated a great deal, implying that the original purchase price substantially understates the true value of U.S. holdings. Because many foreign holdings in the U.S. were acquired quite recently, the original purchase price more accurately reflects the value of foreign holdings.[주1] Nevertheless, while the value of U.S. net indebtedness is not precisely reflected in the statistics, most analysts would agree that the U.S. is currently indebted to the world and that U.S. indebtedness is growing at an unprecedented rate.

One simple conclusion to be drawn from Char 2 is that increases in indebtedness do not necessariy signal bad times; conversely, decreases in indebtedness do not necessarily signal good times. For example, the most rapid increase in the credit position of the U.S. occurred at the beginning of the Great Depression, certainly a low point in U.S. economic history. In contrast, the U.S. moved steadily toward indebtedness during the 1950s and 1960s─two relatively prosperous decades.

Some indication of what has caused indebtedness to swing widely since the Civil War can be gained by examining the behavior of saving and investment over this period. Chart 3 shows national saving, gross domestic private investment, and government saving as shares of national income. While private saving is not presented in the chart, it can be derived as national saving minus government saving.

Chart 3: National saving, government saving, and investment

Investment and national saving reached record rates near 20% as net indebtedness peaked in the early 1890s. The period between 1890 and the middle of the Great Depression was one of decline from these record levels in both saving and investment. This decline was associated with a rapid fall in U.S. net indebtedness, especially during WWI and at the beginning of the Great Depression.

U.S. net indebtedness fell during this period because investment declined more steeply than saving. As noted above, the difference between saving and investment, rather than their levels, leads to changes in indebtedness. Thus, as investment suffered more than saving, excess saving flowed abroad, increasing the net credit position of the U.S.

Indebtedness rose sharply during the period of U.S. involvement in WWII. During this period both saving and investment fell sharply, but saving fell more sharply than investment. Thus, there were capital inflows that increased the rate of indebtedness.

The period from WWII to 1982 was one of relatively steady investment, saving, and government deficits. Saving generally exceeded investment during this period, leading to capital outflows. These outflows contributed to a very gradual increase in the dollar value of the U.S. net credit position with the rest of the world. Because income grew more rapidly than the net credit position, however, the size of the net credit position as a share of income declined steadily.

The most striking feature of the period since 1982 is the sustained excess of investment over saving. The capital inflows required to finance the excess of investment over saving from 1983 to 1987 have averaged over 2.5% of income. These inflows exceed over a percentage point any capital inflows sustained since the Civil War. The only previous periods since the Civil War when capital inflows have exceeded even 1 percent of income were from 1884 to 1893 and again in 1943.

This review of history gives mixed signals about the implications of the recent surge in U.S. indebtedness. It may be comforting that large swings in indebtedness have occurred before, and that some periods of rising indebtedness have been associated with good times. However, the fact that the current capital inflows are without precedent is disconcerting. The next section explains the central role investment play in determining whether indebtedness will enhance or diminish growth in living standards.

II. The Importance of Investment to Debtors

The essential reason why investment is important to debtors is the same for individuals, businesses, and countries: successful investments yield income. Suppose a country uses borrowed funds to finance investment projects and that these projects generate more than enough income to pay the interest on the loan. In this case the debt can be serviced with income left over to increase living standards. In contrast, suppose that a country finances a higher level of consumption by cutting back on investment and by borrowing abroad. In this case, the results could be quite different. (... ...)

(... ...)

A Previous period of indebtedness: the late 1800s

(... ...)

Two views of the current U.S. indebtedness

Those who are optimistic about the recent rise in U.S. indebtedness have argued that something very similar to the events of a century ago is happening in the U.S. today. This contention is strongly debated by a group that foresees more austere times resulting from U.S. indebtedness. The accounts these two camps give of U.S. economic prospects make clear the important role investment will have in resolving this debate.[주7]

^Prosperity ahead?^ The prosperity view of economic prospects begins with the proposition that, since 1982, investment opportunities in the U.S. have been much better than those in 1970s and early 1980s.[주8] Proponents of this view have put forward several reasons for this central proposition. President Reagan was vocal in support of free market capitalism, championing changes in government policies and taxes to benefit businesses. Supporters of supply-side economics believe that these tax cuts and regulatory reforms may have greatly stimulated investment in the U.S. Some analysts have also argued that the deep recession that ended in 1982 enhanced business prospects by promoting efficiency, by moderating wage demands, and perhaps most important, by lowering the inflation rate to under 5%.

According to the prosperity view, the improvement in business prospects has had four implications. First, a boom in investment began in 1983, when businesses became aware of the rosy economic future reflected in these investment opportunities. Second, consumption rose as consumer became more confident about economic prospects. Third, the strong demand for credit to finance the new investment and consumption pushed up real interest rates in this country. Fourth, investors across the world sought to take advantage of the high interest rates available in this country, leading to inflows of foreign capital.

^Austerity ahead?^ The second view of he current situation predicts austerity in the future.[주9] This view of U.S. foreign indebtedness begins with the proposition that the U.S. has cut back saving for the future in favor of consuming in the present. Proponents of the austerity view support their central proposition by pointing to the data on rates of saving and consumption since 1982.

The reduction of government saving is reflected in the budget deficits registered in the 1980s(Chart 4). From 1983 to 1988 the budget deficit averaged 2.9% of gross national product, much higher than the average of 1.0% for the 1954-88 period. In the post-Civil-War period, budget deficits of this size in relation to national income have occurred only during wars and the deepest recessions. The fall in private saving has been smaller. Private saving as a share of national income has fallen to 16.3% in the current economic expansion, down from an average 16.9% in the 1954-88 period, and well under the average rate of 17.1% for expansion since 1954. The counterpart of the decrease in saving has been an increase of over two percentage points in personal consumption expenditures as a share of national income, rising from an average of 62.8% in the current expansion.

[주9] See, for example, Friedman 1988 and Summers 1988

As with the prosperity view, four steps are predicted to follow from the central assertion of the austerity view. First, consumption rises and saving falls. Second, reduced saving reduces the domestic pool of funds available for lending. Third, competition among borrowers for the reduced pool of investment funds drives interest rates upward, squeezing some borrowers out of the market and reducing investment. Fourth, as in the previous account, increased interest rates attract foreign capital.

The predictions of both the prosperity and austerity views of the the U.S. economic outlook are quite similar. Both views predict strong consumption, high real interest rats, and inflows of foreign capital.[주10] Each of these predictions has been borne out since 1982. The debate between backers of these two views has been difficult to resolve precisely because the predictions of the views are so similar. There is, however, one important difference in the two views. The prosperity view predicts strong investment, while auterity views predicts weak investment.

The overall message from this review of the competing views of U.S. economic prospects is that the behavior of investment is among the most important issues determining the effect of U.S. external indebtedness.[주11] If strong investment has been laying the groundwork for rapid economic growth, then widespread concern about foreign debt may be displaced. Rapid economic growth can allow the U.S. to pay interest and dividends on foreign-held assets, while still allowing U.S. living standards to increase. On the other hand, weak investment─investment that is insufficient to support growth─may be doubly bad. Slower income growth, undesirable by itself, is made worse if a significant share of future income must go to pay interest on a large foreign debt.

III. Weak Investment in the 1980s

There has been considerable debate as to whether investment in the 1980s has been weak or strong. Economists supporting the prosperity view assert convincingly that an investment boom has followed the recession in 1982, whereas economists supporting the austerity view make as strong a case that investment has been weak. The opposing camps measure investment differently and apply different standards to determine when investment is strong or weak. This section evaluates these two positions and concludes that investment in the 1980s has been weak.

Before beginning the analysis, however, an alternative approach to addressing the question about investment should not be ruled out. This appraoch involves examining the actual inflows of foreign funds and determining whether or not the funds have been spent on productive capital. Pursuing this line of analysis, for example, would involve analyzing whether the capital flowing from Japan has gone to build factories or to pay for corporate takeovers. This approach is not very useful in evaluating U.S. economic prospects. Total productive investment in the U.S. is the more important issue for economic growth, and it is relatively unimportant whether Americans or foreigners fund the investment. For example, even if all of the foreign funds were spent on productive capital, slow income growth could still result if total investment fell. Thus, this section examines whether the rise in foreign indebtedness has been mirrored by a rise in investment, and it leaves aside the issue of whose money paid for which asset.

The weak if net fixed investment (...)

Net versus gross fixed investment (...)

Misleading investment growth (...)

Weakness of broader investment measures (...)

Implications for the future

Three risks in the current course of strong growth in foreign indebtedness and weak investment can be identified.

(1) The first risk is that weak investment will lead to slower income growth than in the past. As noted above, investment leads to growth in income by allowing workers to be more productive. Productivity growth has been sluggish in the U.S. since the mid-1970s, and weak investment risks further slugishness.

(2) A second risk comes from the burden of indebtedness. If borrowed funds are not used to generate new income, spending in some areas will ultimately have to be cut back to pay the interest and dividends on foreign-held assets in the U.S. This burden is currently not large in relation to national income, but U.S. indebtedness has been growing rapidly in relation to national income. The ultimate burden will depend on how large net capital flows are in the years ahead.

(3) A final risk is posed by the adjustments required to slow the growth of indebtedness. U.S. indebtedness cannot grow indefinitely as a share of nation income; the burden of indebtedness would eventually outstrip the U.S. ability to pay. Just as market forces guarantee that corporations and individuals cannot borrow an unimited amount, market forces will also ultimately halt the growth in the rate of U.S. indebtedness. These market forces may also have detrimental effects on living standards. For example,[:]

(3.1) the interest rates at which the U.S. can borrow may rise, increasing the burden of indebtedness.

(3.2) Further,

the real value of the U.S. dollar may fall relative to other currencies. This would imply that a given dollar value of interest payments to foreigners will represent a larger sacrifice of U.S. goods than before.[주19]

[주19] A description of these effect and their likely importance is provided in Lawrence 1988.

The likely importance of these effects is subject to debate. Some economists contend that growth in living standards will stagnate, while others contend that the likely effects may be small. Choosing between these predictions is difficult, in part because the combination of weak investment and rising indebtedness has persisted for a relatively brief period. (... ...)

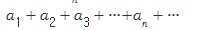

의 각 항을 차례로 합의 기호 + 로 연결한 식

의 각 항을 차례로 합의 기호 + 로 연결한 식

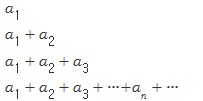

이 수렴하는지 또는 발산하는지 알기 위해서는 부분합의 수열 [, 즉]

이 수렴하는지 또는 발산하는지 알기 위해서는 부분합의 수열 [, 즉]

Keynesian LRAS curve

Keynesian LRAS curve