자료: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Great_Exhibition

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

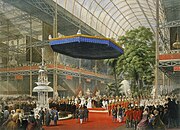

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations or Great Exhibition, sometimes referred to as the Crystal Palace Exhibition in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held, was an international exhibition that took place in Hyde Park, London, England, from 1 May to 15 October 1851. It was the first in a series of World's Fair exhibitions of culture and industry that were to become a popular 19th century feature. The Great Exhibition was organised by Henry Cole and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the spouse of the city's reigning monarch,Victoria of the United Kingdom. It was attended by numerous notable figures of the time, including members of the former French Royal Family and the writers Charlotte Brontë and George Eliot.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Background

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations was organized by Prince Albert, Henry Cole, Francis Henry, Charles Dilke and other members of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce as a celebration of modern industrial technology and design. It can be argued that the Great Exhibition was mounted in response to the highly successful French Industrial Exposition of 1844. Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's consort, was an enthusiastic promoter of a self-financing exhibition; the government was persuaded to form the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 to establish the viability of hosting such an exhibition.

A special building, nicknamed The Crystal Palace,[1] was designed by Joseph Paxton (with support from structural engineer Charles Fox) to house the show; an architecturally adventurous building based on Paxton's experience designing greenhouses for the sixth Duke of Devonshire, constructed from cast iron-frame components and glass made almost exclusively in Birmingham and Smethwick, which was an enormous success. The committee overseeing its construction included Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The massive glass house was 1848 feet (about 563 metres) long by 454 feet (about 138 metres) wide, and went from its initial plans of organisation to its grand opening in just nine months. The building was later moved and re-erected in an enlarged form atSydenham in south London, an area that was renamed Crystal Palace; it was eventually destroyed by fire.[1]

Six million people – equivalent to a third of the entire population of Britain at the time – visited the Exhibition. The Great Exhibition made a surplus of £186,000 which was used to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum which were all built in the area to the south of the exhibition, nicknamed "Albertopolis", alongside the Imperial Institute. The remaining surplus was used to set up an educational trust to provide grants and scholarships for industrial research, and continues to do so today.[2]

The exhibition caused controversy at the time. Some conservatives feared that the mass of visitors might become a revolutionary mob,[citation needed] whilst radicals such as Karl Marx saw the exhibition as an emblem of the capitalist fetishism of commodities. In modern times the Great Exhibition has become a symbol of the Victorian Age, and its thick catalogue illustrated with steel engravings is a primary source for High Victorian design. [3]

[edit]Notable exhibits

Exhibits came, not only from throughout Britain, but also its expanding imperial colonies, such asAustralia, India and New Zealand, and other foreign countries such as Denmark, France andSwitzerland. Numbering 13,000 in total they included a Jacquard loom, an envelope machine, kitchen appliances, steel-making displays and a reaping machine which was sent from the United States.[4]

- Alfred Charles Hobbs used the exhibition to demonstrate the inadequacy of several respectedlocks of the day.

- Frederick Bakewell demonstrated a precursor to today's Fax machine.

- Mathew Brady wins medal for his daguerreotypes.

- William Chamberlin, Jr., of Sussex, exhibited what may have been the world's first voting machine, which counted votes automatically and employed an interlocking system to prevent overvoting.[5]

- The Tempest Prognosticator, a barometer using leeches, was demonstrated at the Great Exhibition

- The America's Cup yachting event began with a race held in conjunction with the Great Exhibition.

- George Jennings designed the first public conveniences in the Retiring Rooms of the Crystal Palace for which he charged one penny.

- The Koh-i-noor, the world's biggest known diamond at the time of the great exhibition

[edit]Admission fees

Admission prices to the Crystal Palace varied according to the date of visitation, with ticket prices decreasing as the parliamentary season drew to an end and London traditionally emptied of wealthy individuals. Prices varied from 3 guineas per day, £1 per day, five shillings per day, down to one shilling per day. The one shilling ticket proved most successful amongst the industrial classes, with four and a half million shillings being taken from attendees in this manner.[6]

[edit]See also

[edit]References

- ^ a b "The Great Exhibition of 1851". Duke Magazine. 2006-11. Retrieved on 2007-07-30.

- ^ The Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851. "About Us". Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ^ A copy of the Illustrated Catalogue is available on Google books at http://www.google.com/books?id=OfMHAAAAQAAJ&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0

- ^ "The Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace". Victorian Station. Accessed 3 February 2009.

- ^ "The Great Exhibition," Manchester Times (24 May 1851).

- ^ "Entrance Costs to the Great Exhibition". Fashion Era. Accessed 3 February 2009.

[edit]External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Crystal Palace |

- Prince Albert's speech of 1849, announcing "The Exhibition of 1851"

- "Memorials of the Great Exhibition" Cartoon Series from Punch

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Great Exhibition

- "In Our Time"BBC radio programme discussing the Great Exhibition and its impact.

- Images from the catalogue on flickr.com

- Charlotte Bronte's account of a visit to the Great Exhibition

- Great Exhibition Collection in the National Art Library

- "Watercolours of the Great Exhibition". Paintings and Drawings. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved on 2007-11-13.

[edit]Further reading

- Auerbach, Jeffrey A. The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display, Yale University Press, 1999.

- Gibbs-Smith, Charles Harvard The Great Exhibition of 1851, 2nd edition, London: HMSO, 1981.

- Greenhalgh, Paul Ephemeral vistas: the expositions universelles, great exhibitions and world's fairs, 1851-1939, Manchester University Press, 1988

- Leapman, Michael. The World for a Shilling: How the Great Exhibition of 1851 Shaped a Nation, Headline Books, 2001.

- Dickinson's Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, Dickinson Brothers, London, 1854.[1]

댓글 없음:

댓글 쓰기