자료: Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vesalius

Publications

Also in 1538, Vesalius wrote Epistola docens venam axillarem dextri cubiti in dolore laterali secundam (exact translation not found) which demonstrated a revived venesection, a classical procedure in which blood was drawn near the site of the ailment. He sought to locate the precise site for venesection in pleurisy within the framework of the classical method. The real significance of the book lay in Vesalius' attempt to support his arguments by the location and continuity of the venous system from his observations rather than appeal to earlier published works. With this novel approach to the problem of venesection, Vesalius posed the then striking hypothesis that anatomical dissection might be used to test speculation.

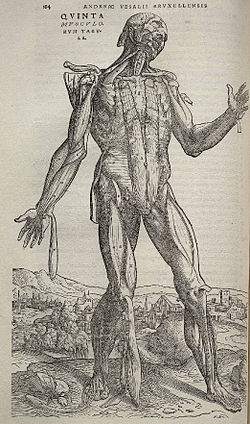

From his work on Epistola, Vesalius moved onto dissect more and more cadavers. The discoveries he made only led him to realize that there were significant contradictions between Galen's text and his own observations of the human form. He spent the next few years working on a composition to highlight his dissections. In an effort to produce what has come to be considered one of the greatest books of the sixteenth century, Vesalius set out to hire the best draftsmen he could find to make the illustrations and the finest Venetian block cutters to produce them. In 1543, Vesalius had Johannes Oporinuspublish the seven-volume De humani corporis fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body), which he monitored carefully, to the extent that he traveled to Basel to oversee the production of his masterpiece. It was a groundbreaking work of human anatomy, which he dedicated to Charles V and which most believe was illustrated by artists working in the studio of Titian, rather than Titian's pupil Jan Stephen van Calcar, who provided drawings for Vesalius' earlier tracts, but in a much inferior style. His book marked the overthrow of traditional Galenic anatomy and acted as a building block for the advancement of modern observational science. De fabrica stands as a major scientific achievement because the illustrations and text set a standard for clarity and accuracy especially in the first two books, which focus mainly on osteology andmyology.

The same year that Vesalius published De fabrica, he created a condensed version of the same book for his students and laymen. This version, entitled De humani corporis fabrica librorum epitome (Abridgement of the Structure of the Human Body) or more commonly known as Epitome, had a stronger focus on illustrations than text, so as to help readers easily understand his findings. The actual text of Epitome was an abridged form of his work in De fabrica, and the organization of the two books were quite varied.

Later, in 1555, Vesalius produced a second edition De fabrica, which was significantly altered in style and the contents were once again rearranged. He added to and corrected his earlier edition by including his observations made over the thirteen years since De fabrica was originally published.

(중략/abbr.)

Scientific and Historical Impact

Modern medicine is forever in debt to the efforts put forth by Vesalius and his ethic to provide the most accurate form of the human body. The manner in which Vesalius tended to his work could arguably be thought of as more significant than the work itself. By overthrowing the Galenic tradition and relying on his own observations, Vesalius created a new scientific method. His desire to strive for the truth is most evident through his ability to correct his own claims and to continually reshape his thoughts on the human body. Through his attention to detail, he was able to provide clear descriptions and unprecedented anatomical drawings that set a new standard for future medical books.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (On the fabric of the human body in seven books) is a textbook of human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) in 1543.

The book is based on his Paduan lectures, during which he deviated from common practice by dissecting a corpse to illustrate what he was discussing. It presents a careful examination of the organs and the complete structure of the human body. This would not have been possible without the many advances that had been made during the Renaissance, including both the artistic developments and the technical development of printing. Because of this, he was able to produce illustrations superior to any that had been produced up to then.

Fabrica rectified some of Galen's worst errors, including the notion that the great blood vessels originated from the liver. Even with his improvements, however, Vesalius clung to some of Galen's errors, such as the idea that there was a different type of blood flowing through veins than arteries. It was not until William Harvey's work on the circulation of the blood that this misconception of Galen would be rectified in Europe.

Vesalius had the work published at the age of 28, taking great pains to ensure its quality. The illustrations are of great artistic merit and are generally attributed by modern scholars to the "studio of Titian" rather than Johannes Stephanus of Calcar, who provided drawings for Vesalius' earlier tracts, but in a much inferior style. The woodcuts were greatly superior to the illustrations in anatomical atlases of the day, which were often made by anatomy professors themselves. The woodcuts were transported to Basel, Switzerland, as Vesalius wished that the work be published by one of the foremost printers of the time, Joannis Oporini.

The success of Fabrica ensured the health of Vesalius' coffers, and in time, fame. He was appointed physician to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V; Vesalius had dedicated the work to the ruler, and presented him with the first published copy (bound in silk of imperial purple, with specially hand-painted illustrations not found in any other copy). The Fabrica was republished in 1555.

A copy of the book clad in human skin was donated to Brown University's John Hay Library by an alumnus. Its cover is "polished to a smooth golden brown" and, according to those who have seen the book, it looks like fine leather. Covering books in human skin was not an uncommon practice a couple of centuries ago, utilizing the skin of executed convicts and poor people who died with no one to claim the body.[1]

Of pharmacological interest, Fabrica mentions Digitalis, which is still an important Inotropic Agent used to treat congestive heart failure.

[edit]External links

- Turning the Pages Online. A U.S. National Library of Medicine project to digitize images and plates from "rare and beautiful historic books in the biomedical sciences".

- Andreas Vesalius. De Humani Corporis Fabrica. Historical Anatomies on the Web.Selected images from the original work. National Library of Medicine.

- De Humani Corporis Fabrica online — translated with full images, from Northwestern University

[edit]References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: De humani corporis fabrica |

- O'Malley, CD. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964.

- Richardson, WF (trans). On the Fabric of the Human Body: A Translation of De corporis humani fabrica. San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1998- (ongoing).

- Vesalius, A. De humani corporis fabrica libri septem [Title page: Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, scholae medicorum Patauinae professoris De humani corporis fabrica libri septem]. Basileae [Basel]: Ex officina Joannis Oporini, 1543.

- ^ some of nations best libraries have books bound in human skin Bosten News 07-01-2006

댓글 없음:

댓글 쓰기